If you want to find out more about the value of urban sustainability and reputation you can read more in the full article here.

What science can tell us about the $40 Trillion question of urban reputation and sustainability

Imagine the blackout across northern India in 2012, the roads jammed with traffic and the train stations swamped when the power shut off for two days in the biggest blackout in history. It had been a sweaty hot summer and as the fans and air conditioners whirred, the power use soared, and then the grid collapsed. This is just one part of the $40 Trillion needed to upgrade water, power and transportation globally over the next 20 years. The World Bank estimate 85% of that will need to be financed by the private sector, and that is why attracting private capital is so important. A blackout in India, or a four-year water crisis in California, or a 5-year-old city for refugees with no infrastructure; they all require funding.

It is in this climate that the investment market is talking about London real estate overheating due to a lack of other outlets. There is no shortage of money and interested parties, including sovereign wealth funds, looking for safe long-term investments – like infrastructure. They are faced with the enormous challenge of finding worthwhile investments because, predictably, they are interested in profitability. Now financial institutions are turning urban sustainability frameworks to help guide their investments. For instance, the Asian Development Bank has developed the index for Environmentally Liveable Cities in China, in order to focus and monitor the impact of investments. It’s clear that urban sustainability is important to the financial community, but do we know why? Let’s peer a little inside the black box to see what science can tell us about the value of sustainability.

What can science tell us about what financial institutions already know to be true, the link between urban sustainability and financial results?

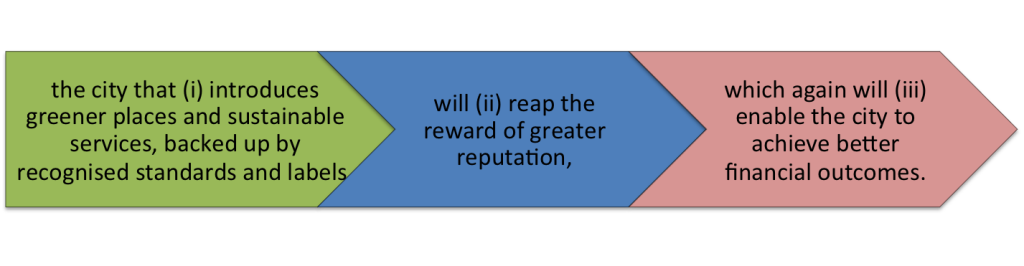

Researchers have investigated the link between sustainability and corporate results. This is our closest parallel to sustainability and urban institutions, since we don’t have direct research to turn to. The Green Business Case Model examines six arguments for the link between sustainability performance and financial performance. This helps lay out our assumption in a neat hypothesis. I’ve adjusted it slightly for cities, not corporations so that it reads:

Hypothesis: the city that (i) introduces greener places and sustainable services, backed up by recognised standards and labels, will (ii) reap the reward of greater reputation, which again will (iii) enable the city to achieve better financial outcomes.

The first part of this puzzle is to see whether sustainably motivated actions improve reputation. An academic paper investigating exactly that found there is a link between the two.

The first part of this puzzle is to see whether sustainably motivated actions improve reputation. An academic paper investigating exactly that found there is a link between the two.

“The study suggests that while environmental processes are substantially important to a firm, such processes are not a significant predictor for corporate reputation. The study demonstrates that environmentally motivated actions on stakeholder sensitivity and environmental marketing are significant predictors of corporate reputation.”

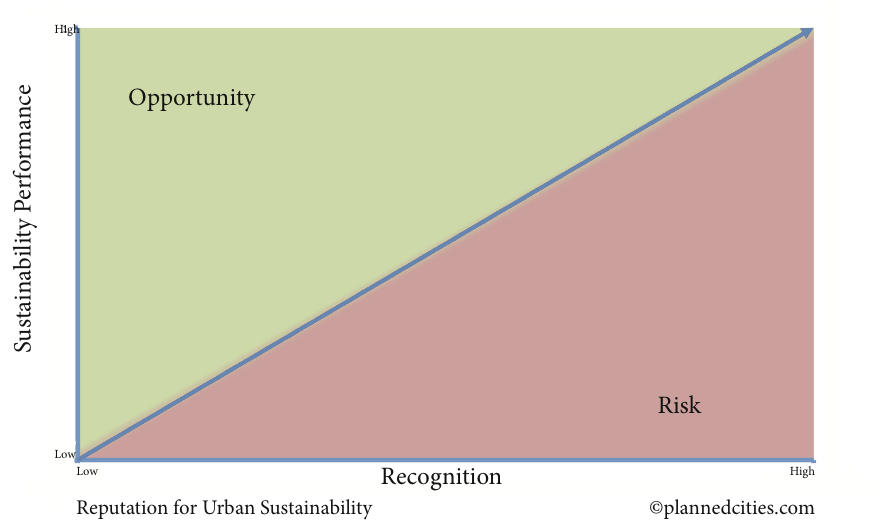

That could be summarised by the following diagram, showing the opportunities related to marketing sustainability, and the risks of ‘discovery’ of poor performance. If you are going to market your urban sustainability, it had better be based on something with substance.

How do urban sustainability frameworks help with the reputation of a city?

Since we know there are two dimensions to good reputation – being well known and have good sustainability performance – selecting a sustainability framework depends on what it is you want to achieve. Let’s take a little time to rate the raters to see which frameworks do what, because among 40+ international urban sustainability frameworks there is plenty of variation.

Three broad categories of tools found by the University of Westminster are ‘Performance Assessment’ frameworks, ‘Certification’ Frameworks, ‘Planning Toolkit’ frameworks.

‘Performance assessment’ describes the measurement of the sustainability of particular places and developments using particular criteria, so as to compare them with other cases, or to track progress over time. This is particularly useful if you want to track the effectiveness of your impact per unit invested. E.g. The Sustainable Cities Index

‘Performance assessment’ describes the measurement of the sustainability of particular places and developments using particular criteria, so as to compare them with other cases, or to track progress over time. This is particularly useful if you want to track the effectiveness of your impact per unit invested. E.g. The Sustainable Cities Index

‘Certification’ frameworks describe a formal accreditation process that may assist both in securing third-party investment and in marketing the development with sustainability ‘kitemark’. They are best suited to external communication of urban sustainability. E.g. Green Star Communities

‘Certification’ frameworks describe a formal accreditation process that may assist both in securing third-party investment and in marketing the development with sustainability ‘kitemark’. They are best suited to external communication of urban sustainability. E.g. Green Star Communities

‘Planning toolkit’ frameworks describe process-oriented sustainability planning within ‘design communities’ of different types. This makes them the preferred approach for improving systems and developing strategies to enhance urban sustainability. E.g. The Community Capital Tool

‘Planning toolkit’ frameworks describe process-oriented sustainability planning within ‘design communities’ of different types. This makes them the preferred approach for improving systems and developing strategies to enhance urban sustainability. E.g. The Community Capital Tool

So which tool you select depends on whether you want to focus on improving recognition or improving performance, because both are necessary to increase reputation.

Case Study: Singapore

In the 1960’s the Singapore River had a rotting stench of garbage, human and industrial waste, the water completely black. Yet, when the founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew past away earlier in 2015, he left behind an amazing legacy and an overwhelming respect for his vision. That is because Singapore has been working diligently for five decades on improving infrastructure. Now it can boast environmental ranking above average for things as diverse as energy and CO2 and transportation and well above average for water quality according to Siemens Green City Index.

The city has been jumping through the rankings across the board. Singapore ranked 4th out of 178 countries in the 2014 Environmental Performance Index, a significant jump from its 52nd place in the 2012 report (EPI report). Singapore is also among the major improvers in the aggregate report of all the leading indices for 2015. Environmental achievements aside, it has overtaken Paris and Tokyo, to be third after London and New York on several indices, and is the world’s number one for business friendliness. (The Business of Cities 2015)

Now a very visible and iconic green project called Gardens by the Bay has been created, which is a 250-acre green oasis overlooking Marina Bay. It is said to have attracted over 15 million visitors since opening less than three years ago. This aligns very nicely with what we see in the reputation scores for the last year; That Singapore’s reputation has improved by almost 10% and is in the top ten cities for tourism for 2015 according to a leading reputation index. Singapore has focused first on sustainability performance and now they are able to increase communicate and market their credentials, and their reputation is increasing with it.

The 6 reasons that city branding and reputation are important

Finance institutions are looking for indications that their investment will be secure, so they are increasingly using indexes to help them achieve this. Reputation relies on a combination of factors, including how well known it is and how well it performs, making it relatively complex assessment of a natural human sentiment. RepTrack make a business of quantifying reputation using surveys and specially selected attributes. Their City model is based on attributes relating to appealing environment, effective government and advanced economy. Unfortunately they don’t incorporate environmental or sustainability performance into their questions. However they do consider beautiful cities and adequate infrastructure as important attributes.

They contend that reputation leads to financial impacts over six categories: intention to visit, invest, live, work, buy, attend/organize events. As the reputation scores increase, the intention to do each of these six activities also increases (with a correlation of over 0.7). Plus the intention score matches very well with measurable results. For example, the intention to visit matches very well with the number of tourism trips.

An aside, that I was completely unaware of until now, was how much money is already spent on city branding. This was an eye opener for me. For instance, London spent a cheeky £74 million between 2003 and 2012 (excluding branding for the London Olympics) on a brand campaign called totally London.

And the winner is…

So next time you wonder why there is strong investment in some places… Like maybe London… Take a second to ponder how much reputation is effecting those decisions.

Armed with the right toolbox, even the poorest cities might well become more sustainable; using infrastructure upgrades to improve their environment and quality of life, while enjoying better and better reputations.

Now you try it

Which city do you live in and what urban sustainability framework does it use? Consider whether it is a Performance, Certification, or Planning framework. You can look for any measurable improvements or categories your city is above average in. Consider whether it is better instead to focus on improvement for the time being or if you can use this to improve your cities reputation. Let me know what you find out.

Real Cities That Help Envision 5 Types of Future Cities

What will our future cities look like? Terms like smart city or resilient city or eco-city seem to be sometimes used interchangeably. What they really mean is how they help us deal with emerging problems.

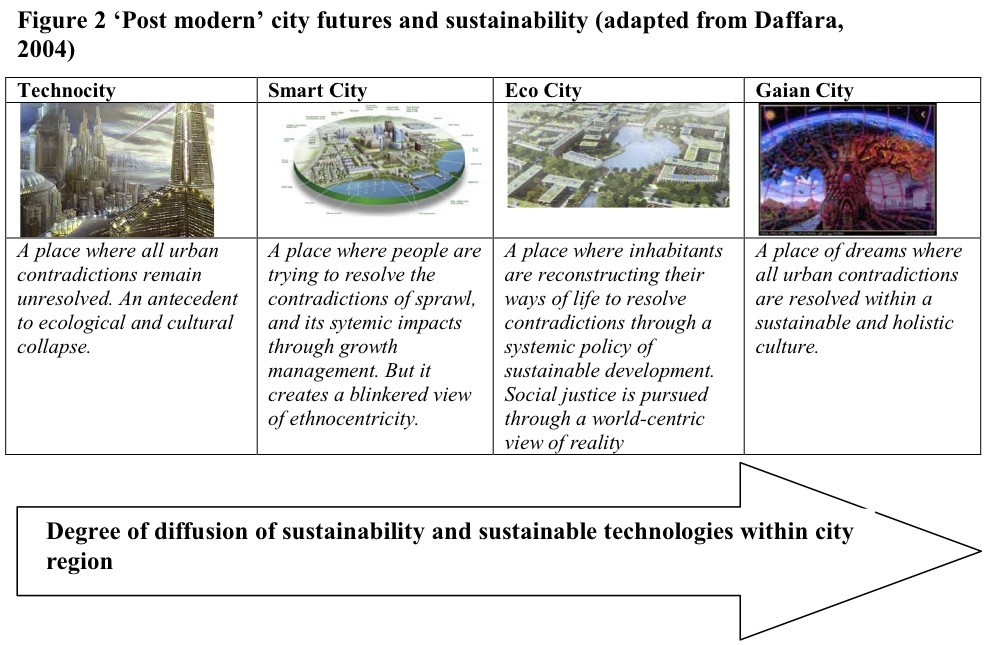

If you search for images of future cities you will find a range of utopian and dystopian sci-fi fantasies. One academic, Daffara, took these metaphors and created city classifications that we can use to examine the solution potential of these ideas. Indeed we can see these ideas reflected in the masterplan solutions presented for new and retrofitted cities. In this article we compare future cities concepts and compare them with their capacity to solve emerging problems.

The problems we identified are: population growth, shortages in consumables including oil, fresh water and food, climate change induced extreme weather events, and the collapse in natural resources. Let’s examine some of the popular types of sustainable cities and what each of those labels implies, and whether they can address those emerging problems. We will do this by looking at examples for smart cities, compact cities, resilient cities, self-reliant cities and eco-cities.

| Population | Shortages | Climate Change | Natural Resources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Cities | x | |||

| Compact Cities | x | x | ||

| Resilient Cities | x | x | x | |

| Self-reliant Cities | x | x | ||

| Eco-cities | ? | x | x | x |

Smart networked cities: Virtual reality meets the real world.

Smart cities are embedded with sensors to monitor real-time usage and provide peak-load dampening, to things such as water, energy, air pollution and traffic. They can also be used for a variety of citizen engagement projects and can be harnessed to provide early warning services and response for climatic events.

While smart cities are able to manage resources more efficiently, they are not intrinsically about including more natural resources into the city. Demand smoothing also might make smart cities less rather than more resilient, and increased complexity has led some to be concerned about the consequences of malfunction or the difficulty of incorporating innovative technology in the future. Smart cities may be too complex to expand to include growing populations.

Songdo is a new city south of Seoul with a sustainability plan, albeit with a lower urban density than Seoul, approaching a density similar to Singapore .

Songdo features:

- Extensive subway system, meticulously timed, displays for arrival & departure times, and with ultra-fast wi-fi

- 40% outdoor green space, 16 miles of bikeways

- Smart rubbish disposal system, underground suction removal system, for a waste to energy system

- Embedded sensors that monitor and regulate temperature, energy consumption and traffic.

- Smart water system to stop drinking water being used in showers and toilets, all the embankments water goes through a sophisticated recycling system.

Future City Example: Smart cities are a popular term at the moment and India has announced that it will build 100 new smart cities. This picture is for the new smart city planned for Dholera SIR in India.

Compact cities: Intensive and efficient urban living, optimizing and reducing demand.

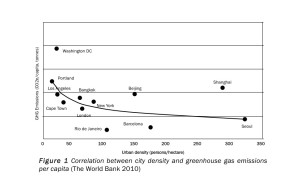

Compact cities are the opposite of urban sprawl and are intended to deal with the twin problems of increasing population and shortages of supply. Making it easier for people to satisfy their needs locally, within walking distance, and making it energy efficient to travel around the city by public transport reduces per capita consumption and higher density houses more people. Compact cities are not intrinsically designed to maximise natural habitat nor anticipate the demands of climate change.

Compact urban forms have received a lot of discussion around optimal density and policy influences. In summary:

- Urban sprawl costs money

- Setting a maximum height has benefits because sunlight is a valuable commodity and low rise (5 storeys) has several advantages

- There is a minimum space that people need for health and wellbeing

If all these three things are held constant then there should be a maximum optimum density, however high rise cities are actually very successful. Seoul in South Korea is a case in point, with one of the world’s highest urban densities, low GHG emissions per capita, and coming 7th on the ARCADIS Sustainable Cities Index and ranking highly for people, planet and profit.

Future City Example: Compact cities are also a popular term for urban master plans. The compact urban form masterplan for the new Egyptian capital city, uses medium and high-density neighborhoods centered on a community public space surrounded by local shops, schools, religious buildings, and civic amenities.

Resilient cities: Future proofed city, robust to the emergent risks of climate change, flexible and responsive land-use, infrastructure and buildings.

While some resilient designs describe maximizing efficiency with smart-city solutions, actually a system with no redundant components has no resilience. These cities will be typified by a belt-and-braces approach. Resilient cities are typically thought of as those protected from extreme weather, however provision for shortages in food, energy and water supply also increase resilience. In a holistic sense, urban resilience is the capacity of individuals, community, institutions and systems within a city to survive, adapt and grow, no matter chronic stresses or acute shocks they experience. This includes earthquakes and floods, but also unemployment and economic stresses. I have written more about creating resilience against these effects here.

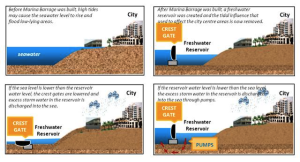

Example: Singapore’s Marina Barrage not only protects urban areas from tidal surges but also creates a freshwater reserve for city water supply.

Future City Example: Already designed and funded, the New York Big U or as it’s colloquially named, the Dryline will be a 16km (10 mile) flood protection system to protect lower Manhattan from events like the 2012 Hurricane Sandy. The 3 to 6 meter high berm will be a semi-permeable barrier of trees, landscaping, and bridges with movable integrated floodwall components.

Self-Reliant cities: Self-replenishing, circular metabolism (cradle to cradle).

Although there are no examples of completely self-reliant cities, several are tackling self-reliance for water or energy. These types of cities may be quite sensitive to fluctuations in population size.

In Scandinavia there are several cities with high sustainability standards, making them good examples of renewable energy, amongst other sustainable infrastructures. While Copenhagen, Amsterdam and Rotterdam all reached the ARCADIS Sustainable City Index 2015, it is Oslo that powers 80% of the city heating system with mainly biomass from residual waste. Sure, other cities like Reykjavik uses only 0.1 % fossil fuels providing power for the city, but the waste use in Oslo is a good example of circular metabolism.

Future City Example: Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, is still only partially complete. In 2006 the Emirati government imagined Masdar as the world’s largest zero-carbon settlement, 5.95km2 in size. It was planned as a self-reliant city, producing it’s own energy, zero-waste and car-free, with vegetables grown on its fringes. After the financial crisis plans changed from self-reliant to low carbon city, with it’s own solar plant, driverless electric vehicles and passive design features, and completion set back to 2025.

Eco-cities: Urban agriculture and harnessing ecosystem services for energy, shelter, water, waste and extreme weather control.

Actual eco-cities are hard to find, yet they are captivating to imagine. Eco-cities use eco-system services to provide for the needs of the inhabitants and have a positive impact on their surrounding eco-system. The concept is simultaneously compact and verdant, and adaptive to environmental shocks. Not necessarily self-sufficient, these cities are producers of resources that can be traded between networks of other cities.

Examining the sustainability initiatives of planned, new and retrofitted cities reveals that eco-cities are often considered to be cities with more open space. In high-density cities around the world the aspirational classes imagine living amongst parks and gardens. This is why Seoul’s neighbouring city, Songdo, has been planned with lower density and 40% open space. Tianjin, another planned eco-city, has abundant green spaces integrated into the urban fabric, even though the World Bank thinks the eco-targets for Tianjin are far from extraordinary compared with some European countries.

Future eco-cities that incorporate vegetation into the urban fabric will probably use a mixture of new building materials and building methods (like 3D printing) to provide green roofs and sky gardens, probably also using algae technology to produce biomass and Oxygen, and hopefully also increase urban agricultural production. All of these technologies already exist although finding them at city scale is a challenge.

- 3D printed buildings

- Green roofs & sky gardens

- Algae technology

- Vertical agriculture

Future City Example: This design is one to stretch your imagination. This design for an underground city in the Nevada Desert captures and stores it’s own water, cultivates vegetation in a harsh environment, and protects inhabitants from intruders.

Summing up

Many cities use catch phrases to describe their initiatives but the goal posts are movable. In China the term eco-city conveys a higher quality, lower density, urban area for aspirational classes. In Europe eco-city means more than protecting the environment, it means utilizing ecosystem services in a symbiotic relationship for people and nature.

It is clear that, while the catch phrases for cities such as smart-city and green-city are sometimes used as synonyms, it does make a difference which term is used. We have seen that real city examples are approaching multiple solutions simultaneously, like Songdo, incorporating green space with smart technology.

Above and beyond which term is used, it is also true that cities need benchmarks. Often we are seeing terms used to indicate high-sustainability that aren’t global best practice. Because openly available consistent data and rankings are lacking it is almost impossible to say which is the greenest or most sustainable city in the world.

Only with proper comparisons between best practices is it possible to understand what are simply popular catch phrases used without substance and what are really sustainable rational investments into city development.

This is part four of a four part series. The other articles are:

http://plannedcities.com/picture_future_cities/

http://plannedcities.com/emerging-risks/

What will future cities look like? Part 3: Adapting Existing Cities

Our existing cities, or “legacy cities”, have been adapted over history to support human civilization. Look at London or Paris, they have adapted many times over to become the cities they are today. Of course Paris has a special story involving Haussmann and Emperor Napoleon III, overcrowding, disease, crime and not a small amount of civil unrest commonly know in those times as revolution. The story of it’s […] [Read more…]

Our existing cities, or “legacy cities”, have been adapted over history to support human civilization. Look at London or Paris, they have adapted many times over to become the cities they are today. Of course Paris has a special story involving Haussmann and Emperor Napoleon III, overcrowding, disease, crime and not a small amount of civil unrest commonly know in those times as revolution. The story of it’s […] [Read more…]

Part 2: Emerging Risks

A number of people, including the insurance industry, think humanity is facing huge risks in the coming years. A recent report by Lloyds explores what might plausibly happen, based on past events, if there were to be a systemic shock to global food crop production (LLoyd’s, 2015). As population increases there will be increasing pressure to match supply to demand. In order to understand why our cities need to adapt let’s take a look at some of the key emerging risks including population growth.